Vito Angelo Colangelo

Vito Angelo Colangelo

The year 2022 marks the 120th anniversary of Carlo Levi’s birth, who was remembered during many interesting events throughout il bel paese, including Turin, Alassio, Lucca and Rome. Obviously, Aliano, the town that the Turin writer immortalised and made world-renowned in his book Christ Stopped at Eboli could not forsake commemorating him.

In the village hidden in Basilicata’s badlands, where Levi was confined by the fascist regime from September 1935 to May 1936, the Turin author’s literary, pictorial and political activities can be revisited through a series of major cultural events that have been painstakingly organised by the managers of the local Literary Park that bears his name, along with those of the city’s administration. The festivities, which will run until 16 May 2023, kicked off on 18 September 2022 with the inauguration of a photographic exhibition by Mario Carbone and an interesting conference that was followed by the performance of the play Luce del Sud [Lights on the South] by Ulderico Pesce.

During this year of celebrations devoted to Levi another very significant anniversary, which curiously coincides with his, cannot go unnoticed, namely the centenary of the birth of Francesco Rosi (1922-2015). The great Neapolitan film director and screenwriter of many well-known masterpieces, including the splendid film adaptation of Christ Stopped at Eboli in 1979.

As many know, soon after the novel was published by the Italian publishing house Einaudi, it became an immediate and resounding success, and the author himself cultivated the idea of turning it into a film. With this end in mind, Levi made contact already in 1948 with a number of producers and directors. After doing so, he initially thought of entrusting the screenplay to Rocco Scotellaro. Levi believed that the young poet and mayor of Tricarico, whom he met on his first return to Lucania immediately after WWII was the person best able to capture the book’s authentic spirit.

He also discussed it with Vittorio De Sica, but after repeated talks the venture went nowhere for various reasons, not least the director's "very exaggerated financial demands,” as we read in one of the numerous letters written to Linuccia Saba and collected in a volume published posthumously. (1)

This brings us to October 1949 when Levi initially thought of turning to Pietro Germi and then to Luigi Comencini, Roberto Rossellini and Carlo Lizzani, but even these attempts didn’t turn out as planned. At Saba’s suggestion, he then thinks of contacting some American filmmakers through his uncle Enrico Wölfer. However, even this attempt fell on deaf ears.

The film would eventually be made only four years after Levi's death on 4 January 1975 in Rome. Francesco Rosi will shoot the film with the screenplay he created together with his close friend Raffaele La Capria and the Romagnolo writer and poet Tonino Guerra. It will be another masterpiece that will be added to the invaluable film collection of the great filmmaker, who at that time, after making his debut in 1958 with the feature film The Challenge had already produced works of extraordinary value to the history of Italian and world cinema such as Salvatore Giuliano (1962), Hands over the City (1963), Men Against (1970), The Mattei Affair (1972), Lucky Luciano (1973) and Illustrious Corpses (1976). After Christ Stopped at Eboli, however, other great masterpieces followed: Three Brothers (1981), Carmen (1984), Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1987) and The Truce (1997).

It bears mentioning that there were two versions of Christ Stopped at Eboli, a 150-minute film version, distributed in cinemas on 23 February 1979 and an uncut TV version of 4 and a half hours, which was broadcasted after the November 1980 Irpinia earthquake in four episodes. Aliano, Guardia Perticara, Craco, and the Matera village of La Martella in Basilicata, along with Gravina and Santeramo in Colle in Puglia were chosen as the filming locations.

The leading actor was, as in many of Rosi's other films, Gian Maria Volonté, here found in the guise of Carlo Levi, whom the director confesses he wanted to use as a thread for the narration of a peasant world that has by now disappeared, overpowered by the tumultuous advent of modernity. Masterful are also the performances of Lea Massari as Luisa Levi and an enchanting Irene Papas in the role of one of the most fascinating characters, a putative witch named Giulia. Finally, among the performances by non-professional actors, mostly local farmers who astounded even Rosi for their surprising lack of inhibition before the camera, is that of Giuseppe Persia, a native of Matera in the role of the tax collector.

Given its remarkable artistic value, it is not surprising that the film received many awards in both Italy and abroad, including a David di Donatello for best film and best director, the Grand Prix at the Moscow Film Festival and the Nastro d'Argento [Silver Ribbon] to Lea Massari as supporting actress. But here we would also like to mention the lesser known but no less significant Carlo Levi Award, which the Maestro collected in Aliano on 31 May 1997 during a sober but emotional ceremony.

Here, I would like to briefly share a pleasant personal memory: In preparing the event program the idea of making a video clip to outline a biographical and artistic profile of the famous director popped into my head. Together with the mayor of Aliano Giuseppe Caldararo, we dared to ask Rosi for material that we could be use towards this end. He generously granted our request and we quickly found ourselves with a splendid volume, which proved to be invaluable for the work we were about to generate. (2)

Without delay and a good dose of self-conscious recklessness, together with friends Vito Caruso and Mimmo Rizzo we went to work and the video clip was ready following exhausting efforts. I must admit that as the crucial moment of its screening approached, the thought of having ventured into a pretentious and perhaps imprudent undertaking became stronger and stronger. Fortunately, it finished well: Rosi not only appreciated the work we had done, but also encouraged us to forge ahead. That video clip, which we entitled The Reasons for a Prize, went on to become an important institutional feature in all subsequent editions of the Carlo Levi Award, even when it later was transformed into a Literary Prize.

That said, let’s return now to the underlying theme, recalling the sweeping and articulate speech full of tasty anecdotes and profound reflections Francesco Rosi gave in Aliano where he reconstructed the story of his film based on Levi's novel. He did not fail to mention that the writer had visited him in 1961 in Sicily in Montelepre while he was shooting Salvatore Giuliano to ask him to direct the film. At that time, however, Rosi had to turn it down for two reasons: First, he envisioned quite a few practical obstacles and second, he simply did not feel personally ready to take on the project.

Franco Rosi finally decided to make the film in 1978, when the time seemed ripe for him to present in new terms and in a changed historical context his personal vision of the ancient, but still current, “Southern Question.” In Aliano he had the opportunity to confirm what he had said in an interview he gave to the Southern Italian journalist Giovanni Russo during the filming of Christ Stopped at Eboli, who integrated it into an interesting essay on Carlo Levi several years later. (3)

Rosi explained that he had not wanted to make a historical film, to evoke the centuries-old evils denounced by Levi in his book, i.e. poverty, malaria and injustices in which the peasants of the South were still suffering throughout the 1930s. Rather, it was his intention to bring to light the serious condition of marginalisation of those residing in Southern Italy, which had persisted during the years of the so-called economic boom. He believed that it was cultural before social and economic in nature and that it constituted a true “cultural genocide.” According to the director, Italy’s left-wing parties were simultaneously co-responsible because they had never helped the peasantry become aware of their weight in history and had, instead, privileged the role of the working class. This political attitude had produced the subtraction of labor forces in Italy’s southern regions with the transfer of masses of peasants from the countryside of the South to the factories in the North, creating a dramatic and shocking phenomenon of urbanisation.

Franco Rosi with his film therefore did not want to nurture an absurd and sterile feeling of nostalgia for an idealised peasant civilisation, but intended to capture the essential values of peasant culture in order to contrast them with the false myths of consumerism and hedonism, which dominated modern bourgeois society and accentuated its moral, social, and economic malaise.

Rosi's Christ, therefore, must be understood as a work which, welcoming and combining the dual dimension, lyrical and essayistic, of Carlo Levi's Christ, does not propose a neorealistic representation of Lucania at the time of the fascist dictatorship, but a critical transfiguration of reality, which aims to restore dignity to human existence in all “the Lucanians scattered throughout the world.” And it does so by recovering the ethical and aesthetic sense of its millenary peasant culture. Rosi's "Christ," therefore, should be understood as a work that, by welcoming and combining the dual dimension, lyrical and non-fiction, of Carlo Levi's "Christ," does not propose a neorealist representation of Lucania at the time of the Fascist dictatorship, but a critical transfiguration of reality, which aims to restore dignity to human existence in all "the Lucanias scattered throughout the world." And it does so by recovering the ethical and aesthetic sense of the millenary peasant culture.

Angelo Colangelo

Translated by Amy K. Rosenthal

(1) Carlo Levi & Linuccia Saba, Carissimo Puck, lettere d'amore e di vita 1945-1969, (ed.) Sergio D'Amaro (Rome: Mancosu, 1994).

(2) See Francesco Rosi, (ed.) Vittorio Giacci (Rome: Cinecittà International S.p.A, 1994).

(3) Giovanni Russo, Carlo Levi segreto (Milan: Dalai Baldini e Castoldi, 2011).

Riproduzione riservata © Copyright I Parchi Letterari

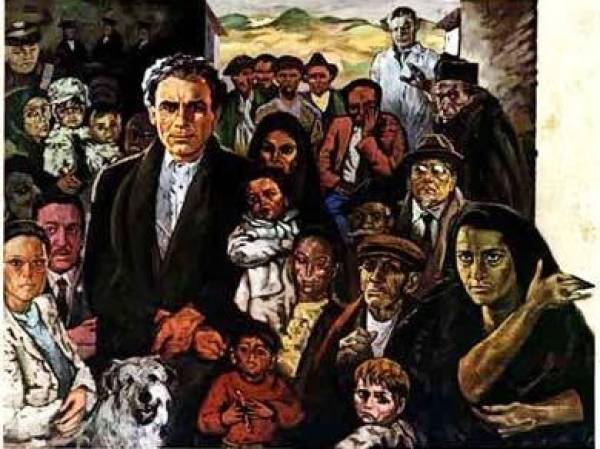

Cover image: cineuropa.org

Trailer : Christ Stopped at Eboli - Rialto Pictures

Sono arrivato a Gagliano un pomeriggio di agosto, portato in una piccola automobile sgangherata. Avevo le mani impedite, ed ero accompagnato da due robusti rappresentanti dello Stato, dalle bande rosse ai pantoloni e dalle facce inespressive. ...

dal Cristo si è Fermato ad Eboli