Vittorio Mascarini

Vittorio Mascarini

The history of Jewish poetry is undoubtedly a unique and extraordinary one, if for no other reason than that it has long been a poetry of exile. However, throughout the centuries of the Diaspora it has not lost its distinctiveness, and this despite the great contribution of new styles, themes and meters borrowed from numerous “guest” cultures, which have instead contributed to making it varied on the basis of their geographical location. One certainly happy example is that of the flourishing of Hebrew poetry in Muslim Spain, where Arabic metrics were adapted to Hebrew and a shift to more worldly themes with respect to the traditional religious dimension began to take place as opposed to the traditional religious dimension that had until then characterised Hebrew lyric poems. But the most curious - and certainly most important - aspect to note in the Sephardic milieu is its attachment to the Hebrew language: if in fact intellectual production tended to be penned in Arabic, over time it began to be translated into Hebrew, thanks to the philosopher Maimonides and the poet Yehuda Ha-Levi.

The Ashkenazi milieu, on the other hand, is perhaps best known for a poetry linked to the religious sphere, although there are countless secular poems of great originality and artistic value. The interesting aspect about Ashkenazic poetry, however, is that it was often written not only in Hebrew, but also in Yiddish. It is in this latter language that we witness, starting from 1500, the influence of themes that mirror those of European literature: for example Bovo-Bukh by the Renaissance Hebrew grammarian Elijah Levita, who wrote a Yiddish translation and adaptation based on the popular novel Buovo d'Antona, itself based on the Anglo-Norman novel by Sir Bevis of Hampton.

In both realities, Sephardic and Ashkenazi, the female presence is certainly in the minority, even if there are examples of great literary significance: from Muslim Spain we are left with some verses in Arabic, handed down by the anthologists al-Suyuti and al-Maqqari, by Qasmuna bint Isma'il, who lived in all probability during the 12th century; in the Ashkenazic world in the 16th century we find instead Rebecca bat Meir Tiktiner, who wrote Eyn Simchas Touro Lid (“A Simchat Torah Song”), a poem with a messianic theme set at a banquet, and Rachel Akerman, author of Geheimniss des Hofes (“The Mystery of the Courts”), a poem about courtly intrigues.

In order to see the full diffusion of Hebrew poetry penned by women, we would have to wait until the age of emancipation, which not only produced an unprecedented era of intellectual development in Europe during the Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment, but would also transform Hebrew into a contemporary literary language. Here, Rachele Luzzatto Morpurgo (1790-1871), a cousin of the well-known representative of the Italian Haskalah Shmuel David Luzzatto, deserves mention. Morpurgo is "the last Italian poet to write in Hebrew,” as the historian Arnaldo Momigliano wrote in his extraordinary tome, Gli Ebrei d'Italia [The Jews of Italy]. In her poems, the poetess from Trieste recounts her inner life, along with her love for the Land of Israel, as well as Jewish life in the diaspora. Vittorio Castiglioni, a noted scholar, native of Trieste, and chief rabbi of the Jewish community of Rome, was so impressed by her poems that he had them published in a 1890 under the title Ugav Rahel (“Rachel's Harp”). Rabbi Castiglioni spoke of Morpurgo as a “ready writer, who by her pleasant writings added beauty and glory to our holy language.”

An historically important boost to Hebrew language poetry and literature came with the advent of the Zionism movement, which advocated for the return of the Jewish people to their ancestral homeland. After becoming aquainted with the latter, Elizer Ben-Yehuda, concluded that the revival of the Hebrew language in the Land of Israel would unite Jews worldwide. With that aim in mind, he went on to devise the first Hebrew dictionary. As the Zionist movement gained momentum, we increasing see the emergence of great poets writing in Hebrew such as Nahman Bialik, recognised as Israel’s national poet, and Naftali Imber (author of Israel’s national anthem), who “rediscover” Israel’s ancient language. But it is with the waves of Aliyah, i.e. immigration of Jews from the diaspora to the Land of Israel, that Hebrew poetry enters an extraordinary phase by becoming inextricably linked with the history of the creation of the Jewish state. One of the most prominent female figure to emerge in this period is Hannah Senesh.

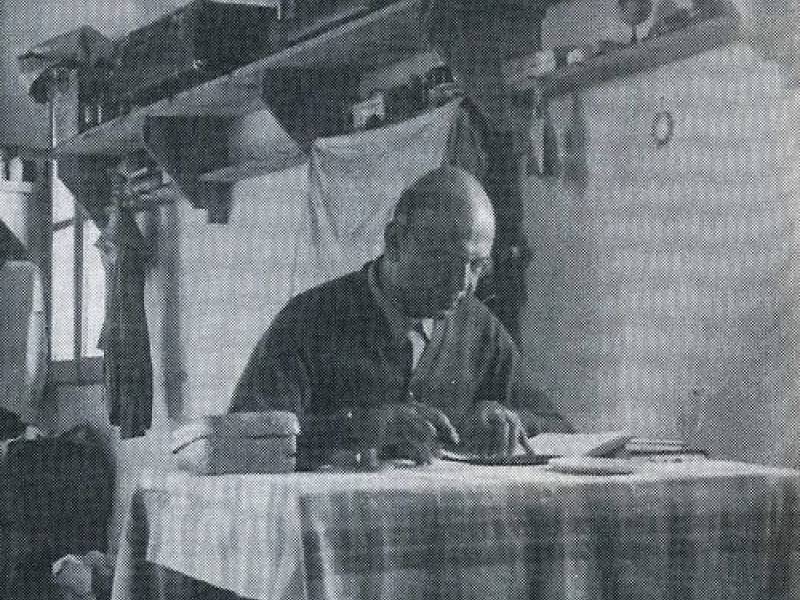

Who was Hannah Senesh? This is not an easy question to answer due to the fact that her poetic activity was as brief as her extraordinary and heroic life. Born in Budapest in 1921, she decided to emigrate with her family to the British Mandate in Palestine in 1941. There, she became a member of Kibbutz Sdot Yam, near Caesarea, where she also joined the Haganah, the paramilitary group that laid the foundation of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). In 1943, she was drafted by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and trained asa parachutist. The Jewish community in Palestine (Yishuv) had expressed a desire to cooperate with Allied forces in the fight against Nazi-Fascism, and the SOE was in charge of organising espionage and sabotage missions across enemy lines. Hannah Senesh volunteered as did many other Jews at the time, including the Italian Socialist Zionist Enzo Sereni, who organised the unit of Jewish paratroopers to which Hannah belonged for these risky missions. In March 1944, together with two other volunteers, she was parachuted into Yugoslavia and then attempted to enter Nazi-occupied Hungary. At the border, she was arrested by Hungarian gendarmes, who found her British military transmitter that she used to communicate with the SOE and other partisans. She was taken to a prison where she was stripped, tied to chair, and beaten for three days. Thereafter she was transferred to a Budapest prison where she was repeatedly interrogated and tortured, but she refused to provide any information apart from her name, even when her mother was also arrested. In November 1944 she was tried for treason in Hungary by a court appointed by the then pro-Nazi and antisemtic Arrow Cross government and executed by a firing squad at the age of twenty-three.

Hannah Senesh was a personality endowed with extraordinary strength, a heroine of the struggle against Nazism and at the same time a pioneer of the kibbutzim, but one should not fall into the error of reading her life along the lines of those "poet-warriors" who dotted the last two centuries of the previous millennium: Hannah was neither a d'Annunzio nor an Avraham Stern and not even a Jewish version of Goffredo Mameli, the Italian patriot, poet and notable figure in the Risorgimento. The characteristic feature of the Jewish poetess was that she embodied a new Jew - one devoted to working the land and defending her people. Senesh's poetry certainly reflects all this, but it is peculiar in that it does so through the filter of individual emotion and the sensations captured whilst admiring the nature of Eretz Yisrael: Hannah Senesh's poetry is a photographic poetry combined with an overwhelming emotional momentum that makes it not simply the poetry of a girl with a short and intense life, but an album that traces an extraordinary life more through feeling than through events. Her most famous poem, "A Walk in Caesarea," has become a symbol of Holocaust remembrance in Israel, as if to remind us that the new Jew embodied by Hannah fights for her freedom:

My God, My God,

May it never end,

the sand and the sea

the rustle of the water

the flash of the sky

the prayer of man.

When we immerse ourselves in Hannah's verses we enter the world of her personal emotions and the historical era - the first kibbutzim and the challenges they faced, as well as their willingness to take up arms during WWII to assist anti-Nazi forces and rescue their people who were being slaughtered across Europe - becomes a backdrop. The last theme written by her hand, which sums up her life as a Zionist pioneer first and a fighter later. is none other than that of sacrifice. Her last poem entitled, "Blessed is the Match," written a few days before her arrest, can be read as an unequivocal testament to her life:

Blessed is the match consumed in kindling the flames,

Blessed is the flame that burns in the secrets of hearts,

Blessed are the hearts that have been able to stop with dignity,

Blessed is the match consumed in kindling the flames.

In the hour of death through the theme of sacrifice Hannah Senesh's inner and outer life fuse, almost recomposing her in her totality: the poet becomes the kibbutz girl and the kibbutz girl becomes the upholder of freedom willing to fight for her people. It is in these last verses that we find the answer to the question "Who was Hannah Senesh?: she devoted her life not only of the Jewish people, but also demonstrates that any person ingrained with a spirit of sacrifice can ultimately prevail by remaining true to their highest ideas and the deepest emotions.

Vittorio Mascarini

Translated by Amy K. Rosenthal

Riproduzione riservata © Copyright I Parchi Letterari

Ph: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PikiWiki_Israel_7704_Hannah_Senesh.jpg